Landscapes

List Gallery Swarthmore College - November 2–December 10, 2017

Donald Teskey: Landscapes brings together a selection of signature paintings by one of Ireland's most celebrated artists. His diverse subjects include landscapes he has observed over extended periods of time, such as the varied terrain of Connemara, County Galway; the canals of Venice, Parisian boulevards, and Connecticut woodlands. Although his prolific 39-year career encompasses diverse media, including drawing, painting, printmaking and watercolor, this exhibition focuses on recent paintings inspired by his ongoing fascination with the the rugged coastline of County Mayo as well as inland scenes from County Cork and the Lee Valley. Paintings such as Tidal Rocks (2017) convey the vertigo one feels at the edge of a cliff, buffeted by wind, trying to behold the scene below. Such images not only dramatize elemental change; they celebrate the elasticity of painting. Spreading large swaths of pigment across the canvas with trowels and palette knives, Teskey synthesizes drawing and painting, representation and abstraction. As he tacks back and forth between evoking specific sites and responding to the unexpected effects of painting, he conveys protean qualities that are beyond time or place. .

Reflecting upon Teskey's gestural seascapes, one might be surprised to learn that he first gained recognition for large and meticulously detailed drawings, including urban scenes rendered with carefully gradated layers of pencil. Born in Rathkeale, County Limerick, Ireland, in 1956, he felt an early affinity for art. His father worked as a custom home builder and he grew up assisting in the family's joinery, where he developed an appreciation for craft. Teskey's family encouraged his passion for art, and he matriculated at Limerick School of Art and Design just as Ireland's art curriculum shifted from a focus on producing art educators to training artists dedicated to their own creative practices. His studies emphasized direct observation and figure study and were informed by texts such as Kimon Nicolaides' The Natural Way to Draw. Drawing not only provided him with a way to develop new concepts; it became his primary medium for more than a decade and remains integral to his process.

Teskey broadened such traditional underpinnings when he other college students participated in a program that allowed them to earn money each summer by picking tobacco in Toronto, Canada. During three trips abroad, he visited New York City, where he was fascinated by artists as diverse as Frank Stella and Chuck Close. Whether looking at representational or abstract works, he felt freed by the pluralism of the art scene. He especially admired artists who activated the spaces between primary forms or motifs, conveying an all-over engagement with space.

Early drawings, such as Ghosts X (1979), reflect Teskey's interest in creating a highly structured composition in which he articulates or textures every element. A lateral band of white papers blows from left to right across a derelict urban lot, evoking a sense of restlessness, dislocation, and absence. In 1980, he exhibited Ghosts X and similar works in his first exhibition at Lincoln Gallery, Dublin. The staccato quality and horizontal emphasis of such compositions prefigured later paintings, such as Longshore VII (2015), in which dramatic bands of white surf brighten the surrounding darkness. early drawings also set the stage for his continuing interest in composing through through strong chiaroscuro, activating the overall surface of works, and exploring the mystery of forms that appear to be in flux.

Moving to Dublin soon after graduating from art school, Teskey encountered a city afflicted by recession and urban blight. Living in Dublin in the 1980s, he found that every second house seemed to border a derelict site filled with wrecked cars and tires. Vacant lots strewn with rubble and detritus provided haunting imagery. He began by making small sketches and taking photographs on site, which he would later assemble into montages in his studio, creating composite and reconfigured views. Teskey developed works such as Migration (1981) using hard pencil, gradually building up layers and rendering details with almost obsessive discipline.

The formality, silvery light, and soft touch of Teskey's early drawings contrasts with the harsh desolation of his subject matter. Blowing papers rise like a flock of birds or a cresting wave, and the absence of figures contributes to a surreal or dream-like quality. Recognizing Teskey's ability to capture the larger cultural milieu or zeitgeist, the American art historian Lucy Lippard included him in the exhibition Divisions, Crossroads, Turns of Mind: Some New Irish Art, which she organized for Williams College Museum of Art in 1984. His works expressed a sense of absence and alienation endemic to a nation that suffered repeated waves of colonialization, strife, and emigration.

Although many of Teskey's drawings portrayed economic hardship, he also remembers the 1980s as a vibrant time in the arts community. Like many of his peers, he survived on the dole and scant meals, but he was soon able to sell drawings, first from Lincoln Gallery and later, Rubicon Gallery in Dublin.

Teskey's work was further catalyzed by the opportunity to teach at the College of Art and Design, which later became the Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT). As he taught painting and life drawing, he urged his students to use all their senses, asking "how do you feel something without touching it?" Increasingly, he followed his own advice and his drawings became more organic, expressive, and animated by strong contrasts of dark and light. When he began painting as well as drawing, he explored a more improvisational mode, trying to locate forms within an overall atmosphere and embracing unexpected marks, effects of light, and interrelationships. "That's how I still paint today," Teskey has stated, "the subject emerges out of this mass, like something being born, gradually working one's way to the surface. If it's not working, you have to go to the core of the subject. Not fiddling around on the surface." 1

As Teskey shifted his focus from drawing to painting, he realized that using a plastering float felt similar to drawing with charcoal—like a natural extension of his hand—and he began to rely upon floats, trowels, large palette knives, and sponges more than detailed brushwork. The broad base of the trowel allowed him to spread large swaths of paint, creating generalized forms, and the trowel's long edge and corner helped define crisp edges or incise lines.

Recent works such as Towards Belderig, (2014) and Longshore VII (2017) reflect the way such tools continue to allow him to establish large swaths of tone and color as well as detailed marks that convey a sense of scale. He also uses large tools to drag paint across underlying pigment so that the broken or scumbled layers mix optically, creating a more vibrant and nuanced atmosphere.

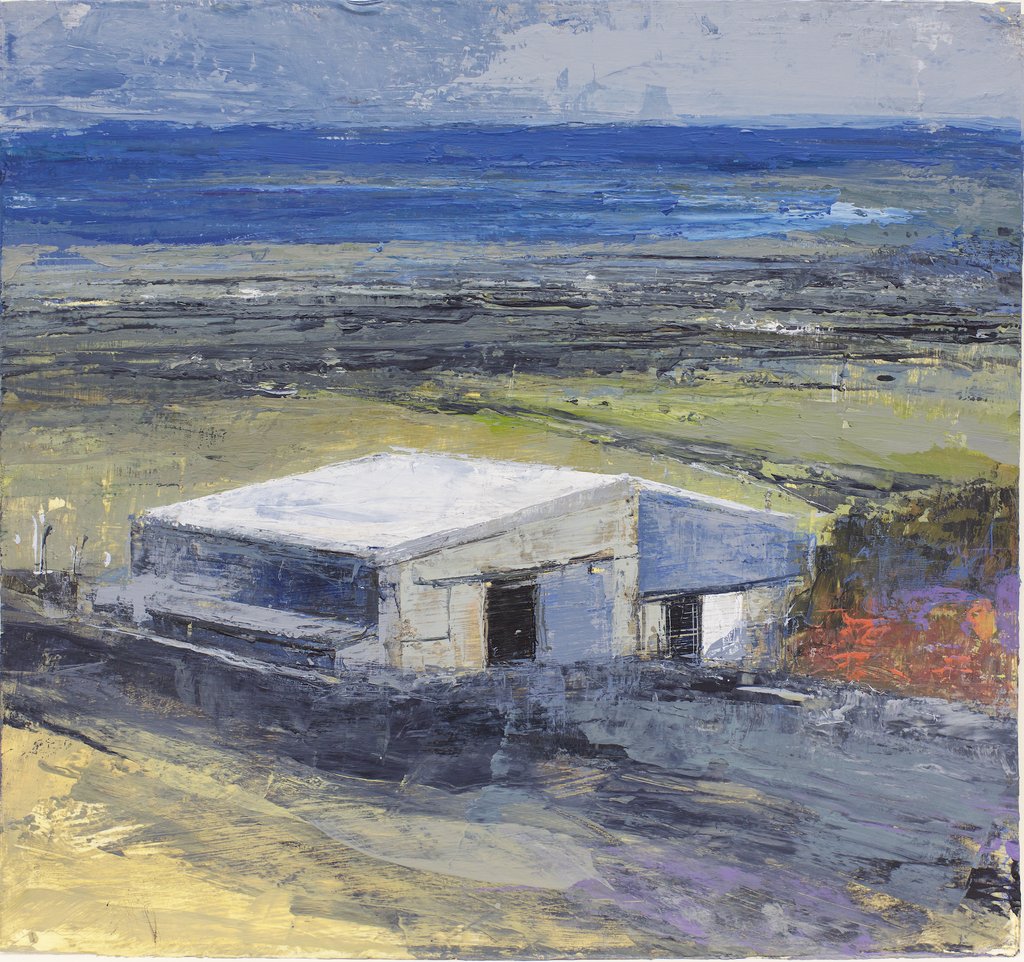

Teskey's use of trowels reinforced his preference for selecting and mixing just a few key colors, often emphasizing a panoply of warm and cool greys. His restrained palette minimizes narrative detail and focuses more on the way distinct elements, be they roads, bridges, houses, or fields, merge within an overall atmosphere and mood. Distinct boundaries and identities become blurred amid the volatile weather. The unifying greys in works such as Erris Head make its single electricity pole and the white rectangular farmstead appear more isolated and desolate. Similarly, the white houses that define the arcing hillside in the middle ground of Gortbrack, North County Mayo (2014), stand out starkly against the distant blue-grey mists and ochre-grey foothills.

For more than two decades, artist residencies have catalyzed Teskey's creativity and allowed him to forge a deep connection to particular places and communities. His first residency, a two week stay in 1995 at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre, Annamakerrig, familiarized him with the landscape of County Monaghan. Subsequently, he pursued longer residencies, including stays at the Gearagh Arts Programme in County Cork; the Vermont Studio Center, in Johnson, Vermont; the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut; and the Centre Cultural Irlandais, Paris. Each opportunity has provided a different terrain for him to explore, be it the sweeping fields of County Cork, the rolling hills and winding river of the Lee Valley, or the varied terrain and mountains of the Connemara.

But no residency or place has had a greater impact on Teskey's work than his 1996 stay at the Ballinglen Arts Foundation in Ballycastle, County Mayo, an experience that led to his a compelling, varied, and ongoing body of work. During his first visit to Ballinglen in 1996, he avoided painting the most obvious motif: the 126-foot-high cliffs of Downpatrick Head and surrounding coastline. Instead, he focused on the main street in Ballycastle, near the foundation's studio buildings. The resulting works capture the way the solid boundaries of the built environment contrast with the fluid conditions of light and weather.

Over more than a dozen subsequent visits, Teskey was inspired by the ever-growing creative community of artists who have worked at the Ballinglen Arts Foundation since its founding 1995 by Margo Dolan and Peter Maxwell. Artists selected from a wide range of applicants work there for a minimum of three weeks during their initial residency and many fellows return subsequently, contributing to a creative dialogue that is interdisciplinary, international, and intergenerational. Extended conversations with diverse Ballinglen Fellows, including American painters such as Stuart Shils, encouraged Teskey to reflect upon the way artists continue artistic traditions rooted in European painting.

Upon his subsequent visits to County Mayo, Teskey began painting the sprawling beaches and towering cliffs. Like many artists in County Mayo, he often felt he did not paint the landscape so much as sudden shifts in light and weather. As he has noted, Ballycastle's geology is spectacular and similar to that of County Clare, but it remains relatively free of tourism and commercial development. As a result, the landscape provides an experience of the sublime in nature that is increasingly rare. As Teskey explored the County Mayo coastline, photography and sometimes videos provided him with memory aids, but drawing and an experimental studio practice remained his primary means for conveying the dynamism of the landscape. As he has stated, "Often, what becomes the basis of a painting is not so much the object of a scene, but the dynamic combination of lines created in the urgency of the drawing process." 1 His paintings do not capture a particular likeness of a place so much as a composite experience of being there over time.

For example, works such as Lighthouse (2017) dramatize a specific motif, but the structure is off-center, and cropped by the top edge of the painting. Instead of commanding the landscape or providing a source of illumination, the structure appears ethereal, precarious, and insubstantial compared to massive cliffs and a distant inlet. Teskey does not illustrate a preconceived concept of a lighthouse. Instead, his image evokes the sensation of standing at a precipice, surrounded by wind-swept seascape in a fading light.

Teskey often chooses viewpoints or composite perspectives that convey a sense of contingency and vulnerability. In works such as On Bolus Head (2015), Teskey eliminates the foreground entirely. Because we can't see where we stand, our aerial perspective appears more uncertain or perilous. In other works, such as Longshore VII, he uses numerous sharply angled diagonals to create the illusion of rapid spatial recession; but instead of joining together at a single vanishing point, they zigzag back and forth, offering competing visual paths to follow. The linear rhythms are jarring, equivocal, and exhilarating as they draw our attention across the vast shore to the drama of breaking surf, and beyond it, a gentler mountain vista.

In still other works, such as Longshore VIII, the drama is closer to the picture plane. We are not drawn in so much as confronted with an oncoming wave. Teskey divides the composition roughly in half between between the darkness of the fractured rocks and the relative brightness of the threatening sea. The wave is recognizable as such but equally so, it is an exuberant painterly gesture, a swath of pigment that appears drawn as much as painted. By eliminating the sky above the wave and tightly cropping our view, Teskey emphasizes a sense of imminent danger. We can imagine, but not perceive what is above or beyond it. As one of many works inspired by wave impacts, Longshore VIII calls attention to the sublime—where we experience both mortal danger and profound wonder before nature.

Teskey's ongoing fascination with the resonant potential of seascapes invites comparison with both the romantic landscapes of J. M. W. Turner (1775 – 1851) and the boldly gestural paintings of Marsden Hartley (1877-1943). But his dense paint surface and expressive paint handling reflect a deeper connection to School of London painters such as Frank Auerbach (b. 1931). In works such as Coastline III (2015), rough edges, broken facets of paint, and overlapping planes of color suggest differences between land, sea, and sky, but they also express an underlying ambiguity and equivocation. Although Teskey's surfaces emphasize flat planes more than Auerbach's thick impasto, both artists paint in a way that integrates the gestural force and open-ended process of drawing. Just as Auerbach's figures are both suggested and obscured by thick layers of paint, Teskey's landscape motifs appear elusive and ephemeral.

The alarming consequences of climate change have prompted many contemporary artists to reevaluate the way they portray nature. Teskey has responded both directly and indirectly to such concerns during his varied career. For example, he recently created a series of drawings of the ocean garbage gyres to illustrate Derek Mahon's book and eponymous essay, Rubbish Theory (2016, The Gallery Press, County Meath, Ireland). In a more surreal or metaphysical vein, Teskey's Ocean Frequency series (2012–present) integrates his early vocabulary of floating papers into his seascapes, synthesizing urban and rural motifs, wildness and artifice.

In the context of such a varied career, the expressive landscapes featured in this catalog and exhibition celebrate those places in nature that still appear unadulterated, beautiful, and worthy of preservation. They embody the protean beauty that we need to understand and care for more than ever. Painted with the hands of a draughtsman and with the spirit of a dedicated student, these works model many of the qualities we require: curiosity, self-reflection, and openness.

(footnote 1 : Donald Teskey in an interview with Mike Fitzpatrick in Donald Teskey: Profile, Gandon Editions, 2005, County Cork, Ireland, pp. 18-19.)